This is a great course, even if I say so myself ????

Here is the link to the online phonics course – https://getintoneurodiversity.com/courses/phonics-in-action/

Phonics and the Art of Reading

This is a great course, even if I say so myself ????

Here is the link to the online phonics course – https://getintoneurodiversity.com/courses/phonics-in-action/

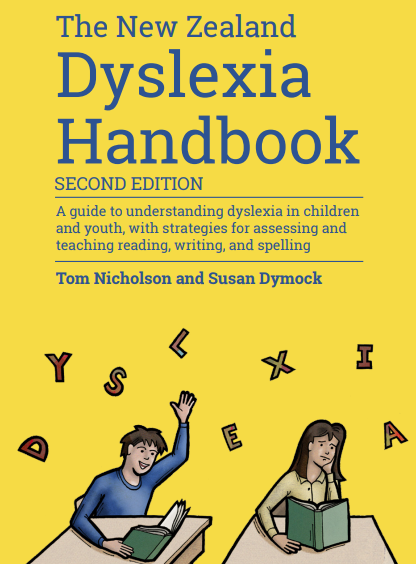

2023 – Dyslexia handbook

One of the interesting discoveries about children starting school is that they often lack phoneme awareness. For example, if you ask a five-year-old school beginner to say the sounds in “cat” they are likely to say “meow”. If you ask them to say the sounds in “nice” they may say, “You’re nice”. Yet lack of phoneme awareness, for many children, may be one of the biggest stumbling blocks in learning to read. This is because when you read words you have to map the letters in the word to their sounds but if you cannot do this, if you do not know what the teacher means by “sound”, then you are blocked. Some children have this skill when they start school but many do not. If they have it, then when the teacher says /k-a-t/ they know it is “cat” because they know words like “cat” are made up of little phonemes. Children with phonemic awareness, can delete the /k/ in “cat” and say what is left /at/ and they can delete the last sound in “cat” /t/ and say what is left /ka/. They can segment the three sounds in “cat” and say them /k-a-t/. They can substitute phonemes, for example , they can replace /k/ with /s/ to make “sat” and replace /t/ with /p/ to make “cap”.

Why is teaching phonemic awareness important?

Some phonics teachers argue that when we teach the letter-sounds of the alphabet (the ABCs) , then phonemic awareness happens automatically as we teach that each letter has a sound (phoneme). Thus, we do not need to teach phonemic awareness separately. Others disagree and say that maybe we should teach it first, but not spend too much time on it. Whatever approach we take, whether we just start teaching the letter-sounds or whether we teach phonemic awareness first, the main thing is to check that the phoneme thing is happening. If children are confused, then best to teach it with some separate exercises. Why is it important? First, it predicts reading success. In a recent meta-analysis (Rehfield et al., 2022) phonemic awareness instruction significantly helped children, especially if taught at the same time as the letter-sounds . Second, phonemic awareness is necessary to learn how to read. It is not sufficient but it is necessary (e.g., Ehri et al., 2001; Gough & Lee, 2007; Melby-Verlag et al., 2012; Rice et al., 2022). The most important skills are blending and segmenting . Deletion and substitution skills may not be as necessary (Clemens et al., 2021).

How to teach phoneme awareness

The first thing is to demonstrate how to make these sounds. Children can make them intuitively but it helps if the tutor shows them how they do it. Much depends on the lips (e.g., /b/), the tongue (e.g., /g/) and sometimes the “nose” (e.g., /m/). For example, /k/ is a popping sound where the tongue is at the back of the mouth and “pops” the /k/. The /a/ is when the mouth is open and the sound comes out. The /t/ is tongue-tipper, the tongue is at the ridge just above the top teeth and pops a /t/ sound.

Students can practice blending and segmenting phonemes if the tutor shows them how to do it, such as with the illustrations below, where the child has to point to the picture that starts with /k/ (cat), and so on. Another activity is if the adult points to three pictures and the child blends the beginning sounds together e.g., a-ant and t-tin make /at/. OR, the tutor can point to 2-3 pictures that make a word, e.g., m-mop, a-ant, t-tin. The child figures it out, = /mat/. Another activity is “odd one out”, e.g., the child has to decide, “Which picture does not match – cat, hat, mop (answer is mop).

Conclusion

Teaching phonemic awareness will help children to succeed in reading. It is not enough but it is a necessary part of the puzzle. The student has to know how to match phonemes to the letters of the alphabet. This is part of the alphabetic principle needed to read words. There is much variance in student phonemic awareness at school entry and teaching can improve phonemic awareness. A suggestion to the tutor is focus on two main skills – blending and segmenting and make phonemic awareness part of the instruction when teaching the 26 letter-sounds.

It can be confusing whether to spell a Latin word with -ian or -ion but there is a rule to help. The rule says that you spell –ian at the end of the word if it is someone who does something – e.g., a magician does magic – but it is -ion if the word does not do something, like “station” or “nation”, they mean something but they are not people who do things like magician, electrician, physician, tactician. Watch the 3m video clip below – it shows how to teach -ian.*

If you would like some more spelling hints, there is the new edition of New Zealand dyslexia handbook (NZCER Press, 2023).

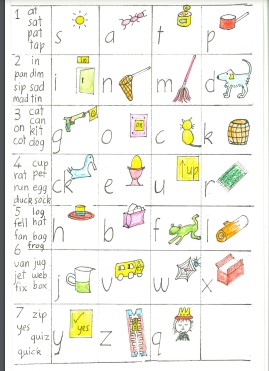

Teaching the ABCs and how to read VC (vowel-consonant) and CVC (consonant-vowel-consonant) words with letters SATP – some suggestions.

For beginners, start with line 1 of the chart. Explain each letter-sound, e.g., this is — /s/. This is /a/. This is /t/. This is /p/. Students practice saying the sounds when you point to them, s-a-t-p. Students practice sounding out words on the sidebar, a-t at, s-a-t sat, p-a-t pat, t-a-p tap. Teacher can point to letter sounds and students say what the word is, e.g., teacher points to a, points to t – the word is —- “at”. Keep up the practice until students can read all the letter-sounds on lines 1-7 and sound out all the words on the sidebar.

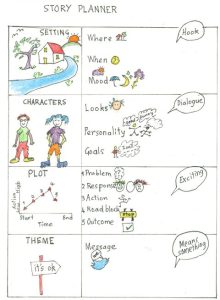

When you write a summary you restate the content in a way that brings out the most important information and also engages the reader.

Summary of a story – You must include in just 100 words 5 key things: a hook to engage the reader (e.g., if you like dogs, you must read this story), then describe the setting (time and place), the characters (who they are, their personalities and appearance), the plot (problem, action, solution), and finish with a theme from the story (e.g., this story showed that if you try hard, you can succeed)

Summary of an article – you must include in just 100 words 4 key things: a hook at the start (e.g., here are some tips for owning a dog), 3-5 sub-headings (e.g., kinds of dogs, caring and feeding, hearing and sight, enemies, keep on a leash), an engaging conclusion (I hope this has helped you know more about dogs).

Final point – Be sure to give a title for your summaries – it is easy to forget this, but very important to catch the attention of the reader.

Try this planner for writing a story summary:

Further reading

Nicholson, T. & Dymock, S. (2018). Writing for impact: Teaching students how to write with a plan and spell well. Wellington: NZCER Press.